Five wood pigeons feast on plum blossoms in a suburban Auckland garden, an increasingly rare sight that stops Jonathan Eriksen in his tracks. For the veteran actuary and investment consultant, these moments of natural wonder have become more precious since the pandemic, when the usually bustling streets fell quiet and nature crept back into urban spaces.

“It’s life and it’s beautiful and it’s to be enjoyed and cherished,” Eriksen says. “But also preserved and protected.”

This philosophy helps explain why one of New Zealand’s most experienced financial minds now serves as a board member for the New Zealand Nature Fund, dedicating his expertise to conservation projects. It’s an unexpected turn for someone who has spent over five decades calculating risk and managing investments, but Eriksen sees urgent parallels between financial and environmental stewardship.

“We’re on the cusp of a new age,” he says, speaking from his office in Auckland’s Northcote neighborhood. “The global economy is going through a huge transition. This year I can jokingly say President Trump might want to annex the Auckland Islands the same way he wants to annex Greenland. If he doesn’t, I’m pretty sure the Chinese would want it because they’re relying on fish to feed their 1.4 billion people.”

For Eriksen, these geopolitical pressures make the Nature Fund’s conservation work more urgent than ever. “We have to do this project, and others just as critical, now because otherwise we might not be able to,” he says.

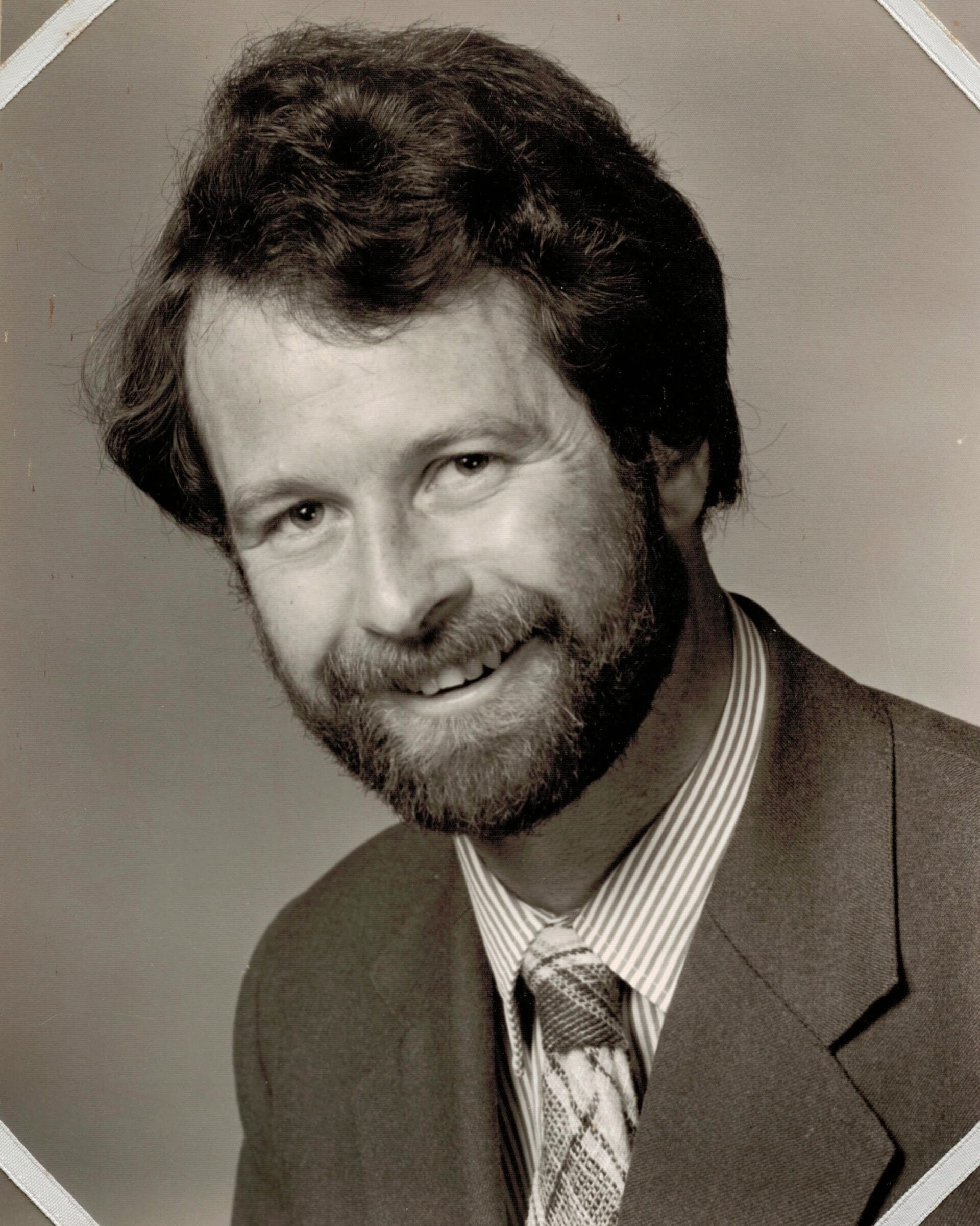

His journey to conservation activism began in the late 1960s, when he abandoned biochemistry studies because “you learn more and more about less and less, and there are no people.” Following his father’s suggestion, he entered the actuarial field, joining the Government Life office in 1968.

Jonathon Eriksen as a young actuary in the late 1960s.

By 1973, he had joined his father’s firm – the first full-time consulting actuarial practice in New Zealand. Over the subsequent decades, Eriksen would help shape the country’s financial landscape, including working with Sir Roger Douglas to design a compulsory superannuation scheme in 1974 that, had it survived a change in government, might have transformed New Zealand’s economy.

“I know, because this is what I do, that had we kept that scheme, New Zealand would be one of the ten wealthiest countries in the OECD,” Eriksen says. The loss still rankles him, driving his ongoing advocacy for retirement savings reform.

Through market crashes and reforms, Eriksen has maintained his practice while witnessing profound changes in New Zealand’s financial sector. He’s seen colleagues lost to suicide during the 1987 crash and watched the transformation of traditional life insurance into modern investment products. His daughter Amy now represents the third generation in the family business.

But it was a chance connection that brought him to the Nature Fund several years ago. A longtime colleague who served on the Fund’s board was stepping down and suggested Eriksen as his replacement. “When I started I was just doing Richard a favour,” Eriksen admits. But the role quickly became more than a professional courtesy.

His time on the board has given him intimate knowledge of New Zealand’s conservation challenges.

Of all the Fund’s projects, he holds a special place for pest control work on Kawau Island. “I’ve spent a lot of time in the Hauraki, and I have seen how swiftly regeneration occurs,” he explains, giving him firsthand experience of both the island’s potential and its vulnerability to invasive species.

Eriksen brings the same meticulous analysis to conservation that marked his financial career. As a board member, he immediately pushed to move the Fund’s investments out of cash and term deposits to generate higher returns – though he readily admits when market conditions proved his initial instinct wrong. “Then it turned out rates went up and actually term deposits were a very good place to invest the money,” he says with characteristic frankness.

This willingness to adapt while maintaining core principles has served him well across his career. He’s witnessed seismic shifts in New Zealand’s financial landscape, from the rise of computer-driven analysis to modern investment products. Through it all, he’s maintained that the fundamentals of his profession are remarkably simple: “It’s discounted cash flows and probabilities. That’s all there is.”

Now he’s applying those same analytical skills to conservation funding. His current focus is securing support for an $80 million conservation project in the subantarctic Auckland Islands, to ensure ongoing viability. “The project is incredibly important, well-planned, and ready to go. It just needs additional funding. That seems like a challenge we can solve.”

Despite the technical nature of his day job, Eriksen finds deep personal meaning in conservation work. During COVID lockdowns, he delighted in the return of native birds to his neighbourhood – grey warblers, tuis, and wood pigeons making appearances in unprecedented numbers. These experiences strengthened his conviction that protecting New Zealand’s natural heritage is crucial.

“We’re here to look after the planet,” he says, “and quite frankly, humans have done a lousy job over the last couple of hundred years.”

At an age when many of his contemporaries have retired, Eriksen maintains his actuarial practice while increasing his conservation work. He’s gradually reducing his professional commitments to dedicate more time to the Nature Fund, recognising the urgency of its mission. “There’s still only 24 hours in the day,” he notes wryly.

His dual roles in finance and conservation give him a unique perspective on New Zealand’s challenges. While he continues advocating for retirement savings reform, arguing for changes to tax treatment that could transform the country’s savings culture, he’s equally passionate about protecting wild places for future generations.

This intersection of financial expertise and conservation ethic makes him a powerful advocate for the Nature Fund’s work. He understands both the practical challenges of funding conservation and the moral imperative to act. As global pressures mount on New Zealand’s wild places, from climate change to resource competition, Eriksen’s combination of financial acumen and environmental commitment becomes increasingly valuable.

“I’m an optimist and I have hope,” he says, despite his clear-eyed view of the challenges ahead. That optimism, tempered by decades of professional risk assessment, may be exactly what New Zealand’s conservation movement needs.

Looking out his office window at the native bush of Northcote, Eriksen reflects on the changes he’s witnessed in both finance and nature over his career. The wood pigeons have moved on from his plum tree, but their visit remains a powerful reminder of what’s at stake. For this veteran actuary, the calculations are simple: New Zealand’s natural heritage is an asset that must be protected, no matter the cost.

Jonathon Eriksen.